Last Updated on August 1, 2020

Many grocery shoppers like knowing about the products they buy, and we often receive questions about Aldi products, including whether or not certain products are fit for certain dietary restrictions.

Many grocery shoppers like knowing about the products they buy, and we often receive questions about Aldi products, including whether or not certain products are fit for certain dietary restrictions.

One question we’ve seen more of late is where Aldi US sources its food products. Or, rather, we’ve received more questions of late asking if Aldi’s products come from a certain place outside of the United States. Nearly all of them specifically ask about — or strongly hint at — one country in particular: China.

Now, it probably goes without saying that Aldi gets a number of its non-food items from China, including things like hiking boots, exercise equipment, and shower caddies. No surprise there. (Aldi also runs a couple of grocery stores in China.)

But what about food? Does Aldi US source its food from outside the United States?

Here is the official word from the company:

In accordance with US labeling requirements, products made outside of the US have their country of origin clearly stated on the packaging. Products with no listed country of origin are from the US, however, they may contain one or more components made, manufactured or produced outside of the US.

U.S. Labeling Requirements

Two government agencies in the United States enforce U.S. product labels: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), a division of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Because of the way the various laws were written and implemented, it’s possible that a product label that would pass regulation under one agency might not under another. Therefore, product labels have to meet the regulation of both to be allowed.

The CBP is guided in large part by the Tariff Act of 1930, also known to history buffs as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. This act, among other things, requires many products from outside the country to bear origin labels. (That’s where your famous “made in China” labels on non-food products come from.) While many food products are covered by the act, there are exceptions, including coffee, tea, spices, produce, nuts, and berries. In addition, if a product is “substantially transformed” at a second site, that second site becomes the country of origin. Under these rules, a car whose parts come from one country but is assembled in another may be able to declare the second location as the “country of origin.”

However, when it comes to food there is more to the story. In the 2000s and 2010s, Congress passed a series of laws that specifically dealt with food labeling, and these regulations are handled by the USDA. These food labeling requirements are known as COOL, which stands for Country of Origin Labels. According to the USDA, COOL regulations require specific labeling for the following grocery store products:

- Muscle cuts of lamb, chicken and goat

- Ground lamb, chicken, and goat

- Fish and shellfish (wild and farm-raised)

- Perishable agricultural commodities (fresh and frozen fruits and vegetables)

- Peanuts, pecans and macadamia nuts

- Ginseng

These products must list both where they are from and, if different, where they are processed (i.e. cut, chopped, packaged). For example, according to the USDA, “[W]hen fish are caught in U.S. waters and then processed in a foreign country that foreign country of processing must appear on the package as the country of origin.” Seafood must declare where it was caught and — if it’s outside the United States — where it was processed.

We’ve seen this repeatedly with Aldi fish and shellfish. We have, for example, reviewed Aldi crab legs that were wild caught in the Atlantic and processed in Canada. We have reviewed breaded fish fillets that were produced in the Netherlands and packaged in the United States. And we have reviewed flounder and stuffed clams that were both caught in the United States and processed in the United States.

Breaded fish fillets nutrition information. Note that it is produced in the Netherlands and packed in the USA. (Click to enlarge.)

We’ve also seen it with other products on the list. My Aldi cocktail peanuts, for example, are a product of the United States but were processed in Canada.

In short, if any of these products are from or processed outside of the United States, they must say so.

Processed Foods

Here things can get a bit confusing, because the USDA uses the word “processed” in two different ways. There is food that is processed, like we saw above, and there are “processed foods.”

Food that is “processed” is food that is, say, cut up. The USDA sometimes calls this food “substantially transformed.”

On the other hand, a “processed food” is defined by the USDA as “specific processing steps that result in a change in the character of the covered commodity.” The USDA cites a few examples, including “cooking, curing, smoking, and restructuring.” (Marinated, salted, or trimmed products would not be considered processed food.)

Processed foods are excluded from COOL origin label laws. From the American Frozen Food Institute:

So called “processed” food items are exempt from COOL. A commodity is considered a processed food item if the processing changes the character of the commodity, or if the commodity is combined with another covered commodity or substantive food component (e.g., chocolate, breading, tomato sauce), except that the addition of a component (such as water, salt or sugar) that enhances or represents a further step in the preparation of the product for consumption would not in itself result in a processed food item. Specific processing that results in a change in the character of the covered commodity includes cooking (e.g., frying, broiling, grilling, boiling, steaming, baking, roasting), curing (e.g., salt curing, sugar curing, drying), smoking (hot or cold), and restructuring (e.g., emulsifying and extruding).

However, processed foods may still be subject to the origin labels run by the CBP. In other words, a processed food from Bolivia that isn’t modified in any additional ways in the U.S. might have to declare Bolivia as its country of origin.

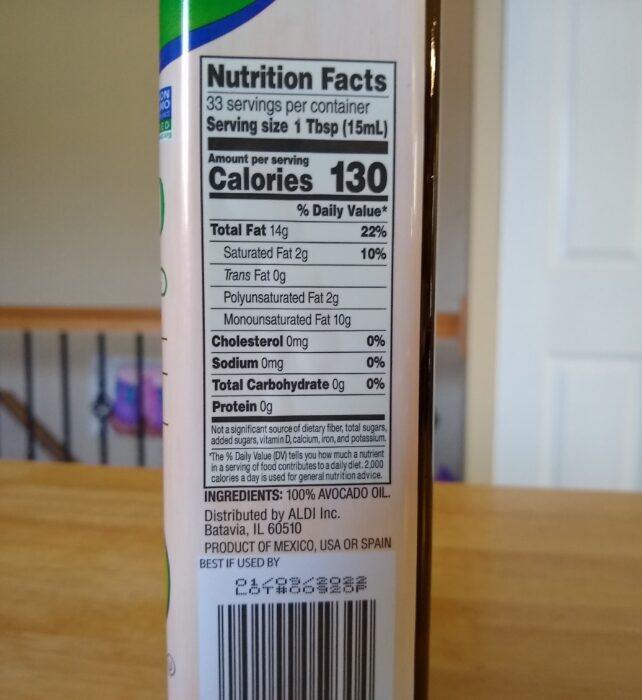

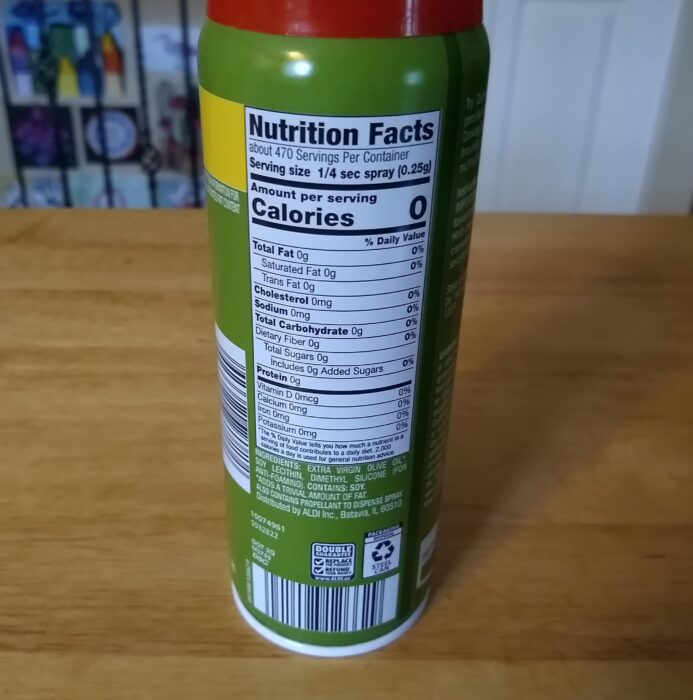

We’ve noticed that our cooking oils from Aldi list countries of origin, but our cooking sprays, which are from a can, do not. We would assume the cooking spray uses imported oils, but because the can is most likely assembled in the United States and the oil is processed into a spray, the can doesn’t need to specify where it or the oil came from.

Ingredients and Components

Aldi concedes on its website, quoted earlier in this piece, that products from the United States “may contain one or more components made, manufactured or produced outside of the US.” Does that mean the packaging or an ingredient could come from outside the U.S.?

I looked around to see if I could find any guidance from the USDA on component ingredients. I could not, so I sent an email to the USDA to see if they could help. My question read, in part:

Do companies have to disclose the origin of seasonings and spices that go into an unprocessed food? For example, if a fish is caught off the coast of Alaska and is processed in Canada, it would be shown as caught in the US and processed in Canada. However, if that fish was marinated as well (which according to USDA rules does not make a food processed), and the marinade came from, say, Italy, would the packaging have to disclose the origin of the marinade or the origin of the marinade’s component ingredients?

I never received a response from the USDA.

What About Pork and Beef?

Pork and beef used to be part of the list as well, but in 2016 they were removed. There have been some bipartisan efforts to revive that rule, but so far they have not passed Congress. That means that, in theory, that beef or pork from outside the U.S. that is processed in the U.S. would not have to declare its origins. The same would go for imported beef and pork that is made into a processed food, like jerky.

As a matter of practice, most beef sold in the U.S. is produced and packaged in the United States. Over 90% of all beef in the U.S., for example, is domestic. Of the imported beef, nearly 90% of that comes from either Australia, New Zealand, Canada, or Mexico. Australia and New Zealand seem to be big exporters of grass-fed beef, so that may account for at least some of those countries’s beef.

Like beef, most pork sold in America comes from American pigs. Part of this is because of the situation in other pork-producing countries: Chinese pork, for instance, is currently illegal for importation to the United States because of concerns over African Swine Flu.

Some people have asked us if U.S. producers raise U.S. pork or beef, send it overseas for processing and packaging, and then send back here. The answer is, probably not. As a representative for U.S.-based chicken processors explained:

Economically, it doesn’t make much sense. Think about it: A Chinese company would have to purchase frozen chicken in the United States, pay to ship it 7,000 miles, unload it, transport it to a processing plant, unpack it, cut it up, process/cook it, freeze it, repack it, transport it back to a port, then ship it another 7,000 miles. I don’t know how anyone could make a profit doing that.

Meanwhile, U.S. exports of meat to foreign consumers are on the rise. In late 2019, for example, Smithfield Foods apparently began shipping pork to China to meet the pork shortage there caused by their decimated pig population. Around that same time, Tyson Foods began shipping poultry to China to meet increased demand. Keep in mind, though, that in both cases, this wasn’t for the purpose of shipping it back to America: it was because American plants were selling to Chinese grocers, which were experiencing a shortage of those meats.

Closing Thoughts:

If this all sounds a little confusing, I agree. It is. The law is complicated. On one hand, certain products, like raw chicken, fish, shellfish, vegetables, and nuts, have to include labels indicating both the product origin and the location of processing. On the other hand, processed foods have different standards, but many imported processed foods still have to declare origin under customs law. All of this is managed by different laws and agencies that overlap in some areas but not all.

Another important point: much of the concern by Americans over food origin is because of concerns about food safety. After all, not every country has the same level of food regulation as the United States. However, it’s important to remember a few things:

- Imported foods are still subject to the same health inspections as domestic foods. The U.S. can and does prohibit some or all foods from certain countries over various health or ethical concerns. (The subject of how U.S. health inspections work, or the conditions on American corporate farms, is another whole post in and of itself.)

- Just because food is raised and manufactured in the United States doesn’t mean it will never have problems. In the last few years, we’ve covered several recalls and problems with American-made food, including romaine lettuce, frozen fruit, and even flour. Don’t forget to practice food safety, such as cooking meat to recommended temperatures and storing food at proper temperatures, regardless of the product’s origins.

- Most of the recalls and health scares we’ve seen in recent years have been over raw produce, which is usually not cooked in the way meat or poultry is. (Most meat illness is from raw or undercooked meat.) Raw produce is required by law to list the country of origin.

Aldi, as best as I can tell, is following the law as well as any other grocer, and Aldi product labels are as informative as any other grocers’ labels I’ve seen. That said, you can always ask Aldi if you have questions about specific products (we’re not Aldi, after all) although I can’t guarantee you’ll learn much more than we did.

EDITOR’S NOTE: As always, we welcome comments, but please keep in mind our community guidelines if you choose to comment.

Thanks for the information. I was looking into where the vegetables and fruit are actually from. May say ‘Batavia, IL. Are they really grown here or are they repackaged somehow? I would like to avid vegetables from AZ and CA.

Most fresh fruit and vegetable packaging at Aldi will say where it is grown. Batavia, Illinois, is Aldi headquarters in the U.S. and not where anything is grown.

thank you… I would still like to see Aldi put country of origin no matter what the regs say. Are these olives from California or Italy? does not say, so I assume California?

Best practice would be for Aldi to be PROactive in labeling country of origin for everything… consumers would value it. IMO